Bluegrass Guitar: Rattling the Leaves Off the Trees

Flatpicking a break on an unamplified acoustic guitar in a bluegrass band is not an easy task. The odds are that your arms are burning because lactic acid is already building up in the striated tissue that makes up the muscles in your forearms. This is all because the banjo player kicked off the tune at 180 beats per minute and you have been mashing chords at that rate for the last three and a half minutes. Note that the guitar is ALWAYS the last one to take a break. Don’t ask me why this is the case, but trust me, it is. It is kind of like leftovers – all the other instruments have had their run at it, now maybe let’s allow the guitar to have a break.

So, you now find yourself in the situation of holding a guitar on stage in front of a zillion people, ¾ the way through a song moving at supersonic speed, arm muscles totally fatigued and burning, and the fiddle player nods to you to take a break. You will very quickly realize that the only weapon you have available is a flatpick slamming on a guitar string and even with superhuman strength, it can’t cut through all the shrillness of banjos, mandolins and fiddles. But somehow, you manage to pull off one or two of your best Tony licks and the crowd goes wild.

This is the life of a guitarist in a modern bluegrass setting. We are working our way thru each of the five primary instruments and their roles in the creation of the modern Bluegrass sound. In the previous chapter, we took a look at the bass fiddle. In this chapter, we will review the bluegrass guitar and the important function that it performs in contemporary bluegrass.

My involvement with the instrument started in 1971, when my cousin Roger showed me a few chords on an old Stella guitar. I have been an ad—hoc guitar player ever since with an occasional stint as a guitarist performing in Bluegrass and Old-Time bands here and there.

Bluegrass Guitar 101

Historians think the guitar originated as a Spanish instrument and was derived from the lute. It was brought over to the new world, maybe via Germany in 1833 by C. F. Martin and others like him, and widely introduced into string band music in the Southeastern US during the 1920s. Before then, people were entertained in the southern mountains with only a fiddle or perhaps a fiddle and a banjo. Guitarists such as Riley Puckett, who played in the string band “Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers,” pioneered the “boom-chuck” backup style that serves so effectively in bluegrass music today. If you listen to some of these early recordings (link), you can clearly hear the ring of the alternating bass strings and rudimentary bass runs in Riley’s guitar work.

Let’s quickly go thru a few basics. Production of sound by bluegrass guitarists consists of using a pick striking a steel (or bronze) string. Lester and Carter both used a thumb pick and got a big sound that way and so does Danny Paisley, but most others use a flatpick. In a band setting, the bluegrass guitarist’s chief job is to play chords that accompany the vocalist or instrumentalists. The fullness of a guitar strumming chords pretty much fills in the mid-range frequencies and helps create the “wall of sound” that is so characteristic of bluegrass music. The guitar blends in so well with the other instruments that you don’t really appreciate its contributions to the sound until you hear the hole that is created when a guitarist breaks a string and stops playing to change it.

The basic bluegrass guitar strum is a “boom-chuck.” The “boom” is the downstroke picking of an eighth note on one of the low-pitched guitar strings. The “chuck” is a strummed chord, also with an eighth note time value, and also with a downstroke. Nobody does a plain “boom-chuck” strum anymore unless the song is moving along at a pretty good clip. More modern bluegrass guitar backup patterns add various accents and emphases in the form of strums and licks. A straightforward extension of “boom-chuck” is to add sixteenth notes (played as upstrokes), which sound like “boom-chuck-a” and “boom-pa-chuck-a”. We will discuss these in detail further below.

It’s All in the Timing!

The clean and tasteful execution of a break on a flattop guitar is always nice to hear but driving the rhythm groove is where the guitarist really earns her pay and is an absolutely essential part of the bluegrass sound. They don’t call it rhythm guitar for nothing. It is also where things can start to fall apart if one is not careful.

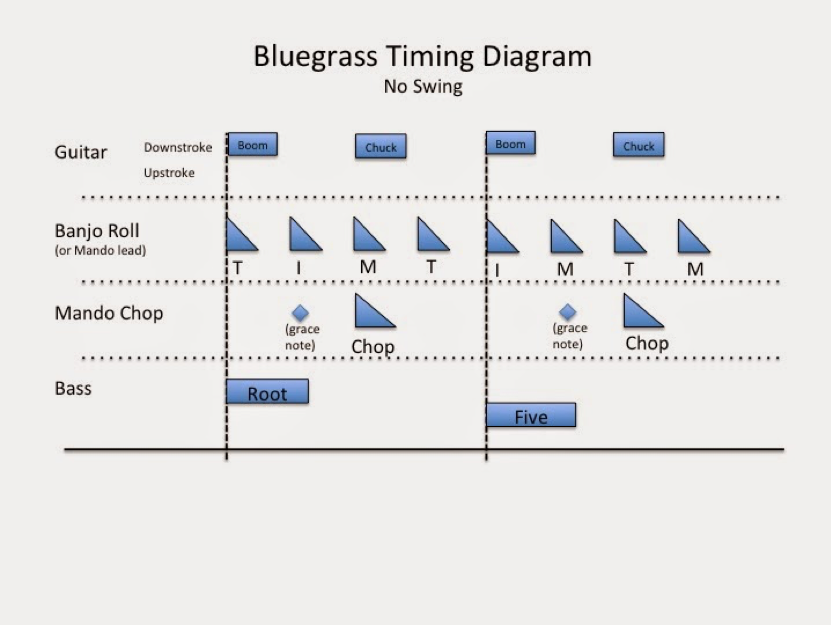

In order to illustrate this concept, we will need to refer to a timing diagram for a bluegrass band. The picture below constitutes a full measure of a bluegrass tune in 2/4 timing. Time flows from left to right.

Going from the bottom of the diagram to the top: The lowest portion represents the bass “root-fiving” – bass notes aligned on quarter notes, played right on the downbeats. Directly above is the Mandolin chop, which occurs on the offbeat. The sixteenth notes of a banjo forward roll are illustrated right above the mando chop.

The topmost layer represents the guitar, which is the subject of our discussion in this chapter. The picture shows the most basic “boom-chuck” strum, the same one that Riley Puckett did back in the ‘20s. Notice that the start of the “boom” aligns with the bass’ thump and the start of the “chuck” aligns with the mando’s chop.

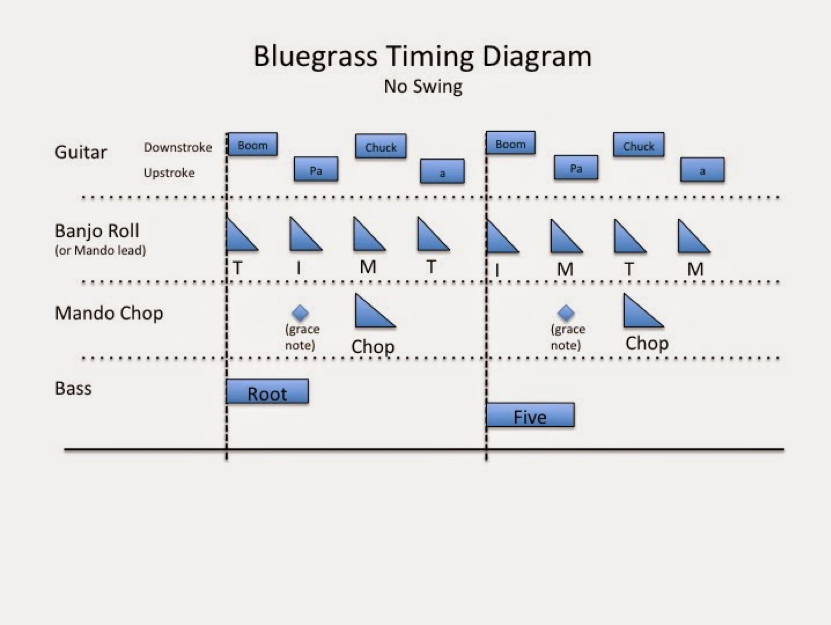

In order to illustrate how a proficient bluegrass guitarist sets up the rhythm for the rest of the band, it will be necessary to add some sixteenth notes to the guitar strum. Let’s look at an exemplary “boom-pa-chuck-a” strum, which consists solely of sixteenth notes (please note again that this is an oversimplified diagram, and that great guitarists will vary their strumming pattern far more than indicated here).

The important point shown in this diagram is that the starts of all of the sixteenth notes are fully aligned from top to bottom. Just like focusing a pair of binoculars, every instrument becomes synchronized, and the resulting sound becomes clear and crisp.

Swing it Baby…

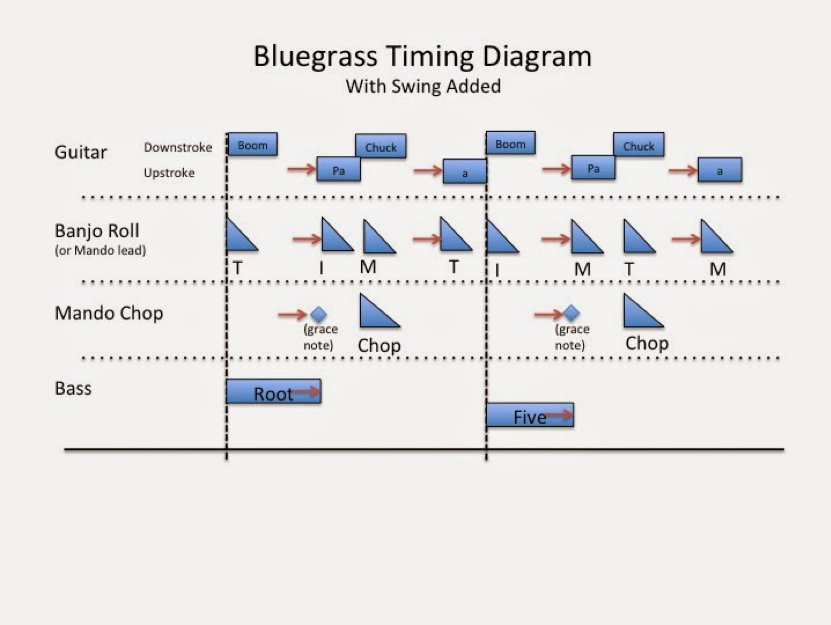

At this point in our discussion, there is no lilt or swing indicated. If executed exactly as shown above, the resulting “music” would sound very mechanical – as if a 1980’s era computer was doing the composing and performing. So, let’s introduce some swing, in order to illustrate what starts to happen in a real bluegrass band.

As the red arrows indicate, both of the sixteenth note guitar upstrokes – the “pa” and the “a” – have moved to the right. Also note that some of the banjo notes have moved to the right an equal amount. In addition, the grace notes that precede the mandolin chop have moved to the right. And the bass notes are lengthened so the end of the note coincides with the new “swung” beat. All these notes are still aligned but occur a few tens of milliseconds later in time.

Before we go any further, I’d like to caution against interpreting all this pedagogy too literally – the definition of “lilt” is far more complex than a couple of swung sixteenth notes. But please bear with me as I use this example to illustrate the power of a good rhythm guitar track.

Setting the Groove

We can now discuss how a good guitarist can really start to define and drive the rhythm for the band. The amount of swing (e.g. the length of the red arrows in the above diagram) will vary depending on the feel that is necessary to make a particular song sound good for a particular bluegrass ensemble on a particular day with a particular phase of the moon. And as we can see from the diagram, the placement of the sixteenth note upstrokes (the “pa” and the “a”) strongly contributes to setting the amount of lilt or swing for our particular song. The competent guitarist will use these types of strokes (and more importantly, lots of other accents and off-beat licks) to assert exactly the right feel for our particular song with poise and style. The guitar strum now sounds something like “BOOOOOM-pa-CHUUUUUCK-a.” Others in the band should follow with this particular amount of swing (among other things) – otherwise, musical notes will sound “out of focus.”

Let’s move to an example. Jimmy Martin was one of the great bluegrass rhythm players (and quite a fashionable dresser) who always made sure his guitar work was featured prominently in the mix. Audie Blaylock, an inveterate Jimmy Martin alumnus, has said that Jimmy’s timing was better than anybody. Have a listen to his 1958 recording of Hold What You Got in the key of F and see if you don’t agree. If you don’t have this recording already in your library, you can find Jimmy performing this recording on stage at a reunion event with JD Crowe and Paul Williams. If you can stand the sight of Jimmy strutting and wiggling, have a look at this video which is a college level course in rhythm and timing.

In the recording (and the stage performance), Jimmy imparts a rhythmic feel with absolutely take-no-prisoners impunity. It starts with him strumming a big fat E position chord (capo on 1st fret) “boom chuck” then “boom-pa-chuck-a” then “boom-chuck-a…” Listen to that last sixteenth note (the “a”) – hear how syncopated it is? When JD comes in with that horrible and annoying melodic style banjo lick, listen to how the notes are placed with exactly the same amount of swing as Jimmy’s guitar strum[1]. And when Jimmy and tenor Paul Williams start singing, listen to how their words are swung in such a way that they exactly fit with Jimmy’s strumming. Buddy Harmon’s snare and Lightnin’ Chance’s bass (yup somebody really named their child Lightnin’) are also completely in sync. Listen in particular to the end of Lightnin’s bass notes and how they end exactly at Paul’s mando chops. The result is a sound that is clean and crisp, and is swinging like Glen Miller Orchestra playing In the Mood back in 1940.

Now that we have seen how things can really click with a strong guitarist, this is a good place to discuss what happens with a perhaps less experienced guitar player. If our inchoate guitar player does not have a good idea of what a particular song needs to feel like rhythmically, and therefore cannot drive the appropriate amount of lilt, then the entire sound suffers. There is no consistent feel being established for the rhythm of a particular song and things generally fall flat. A great rhythm guitar player is something to be thankful for, as she makes a huge contribution to the overall sound.

Punctuation

Let’s get back to the Jimmy Martin theme. All good phrasing has punctuation and Jimmy used to talk about exactly that: The G run kind of punctuation. He used to boast that his G-run would rattle the windows and shake the leaves off the trees. I have no reason to doubt Jimmy on this assertion either. Listen to his version of Uncle Pen. There it is right in the open – the G-run… BOOM! You can’t miss it. In fact, the G-run has become probably the most archetypal series of notes ever to be played in a bluegrass setting. The next time you hear a flatpicking break, I’ll bet that the guitarist punctuates it with some sort of a G-run at the end – make sure you listen for it.

Dynamics is defined as notes, passages and phrases that differ in volume and emphasis (loud/soft). If the G run is the ‘period’ of bluegrass guitar punctuation, then the various forms of dynamics that our guitarist uses are the commas and semicolons. See if you can hear where a strong downbeat is accompanied by a “Carolina Slam” – or a louder than usual guitar strum – perhaps in the middle of a banjo break. Listen carefully to the swelling of volume when the vocalist takes a breath – and then again at the end of the verse, right before the G run. These are but a couple of examples of how dynamics can build on a solid foundation of synchronized syncopation (did I really write that?) to yield a solid and toe tapping performance.

Picking Out the Melody

Since we now have a foundation for the rhythm and groove led by our inveterate bluegrass guitarist, it is now time to start thinking about giving him an instrumental break. One of the earliest and still among the best ways to pull a melody out of a guitar is to use a so-called “Carter Scratch.” Made popular first by Maybelle Carter in the late ‘20s and since copied by many, this technique consists of extending the “boom” notes from the “boom-chuck” strum to include a melody instead of just root-five. Chords are interspersed between the melody notes, so it sounds quite full even with a single guitar. Any guitarist worth a nickel can play Wildwood Flower using a Carter Scratch and this technique actually works quite well on many mid-tempo songs. Here is a link to Mother Maybelle using her eponymous scratch.

Flatpicking guitar became popular in the 1970s, led by Doc Watson, Tony Rice and others. As mentioned in the first paragraph of this chapter, this intricate form of picking is highly demanding. As you might suspect from the name, the technique is, indeed, performed with a flatpick, and a melody is typically played in sixteenth notes with up/down/up/down motion of the pick. If you have a hankering to start flatpicking, remember to follow this “up/down” rule even when seems to make no sense to do so – say if a rest or an extra eighth note occurs in an inopportune place, the pick direction can get backwards on you. Professional help is advised if you can’t sort this out – if you learn to do this wrong, I can guarantee you will not be able to play faster than about 90 beats per minute and it will take years to untangle your bad habits.

Rules however are made to be broken, and crosspicking does just that. Jesse McReynolds pioneered this technique on the mandolin and it has been adapted to the guitar by any number of guitarists in Ralph Stanley’s band, the first one to do so being the late George Shuffler. If you have ever heard him on one of Ralph’s recordings, you know how beautiful this technique can be. Here is a link where Mr. Shuffler demonstrates crosspicking to James Allen Shelton (also of late – tragic losses both) and explains from where he got it. It exactly replicates the 3-3-2 pattern imprinted on the brains of Scruggs-style banjoists, and forces melody notes to occur slightly ahead or behind their usual spots. This fits the very definition of syncopation (covered in the section “Bluegrass Break-down” later in the book) and will cause even the clumsiest among us to want to get up and dance. As with the banjo, it takes hours and hours of mindless practice to do this maneuver with any speed, but once you can do it you will inspire envy in all your friends and relatives.

Tony Rice

No treatise on bluegrass guitar can be complete without a word or two about Tony Rice. Tony was just about singularly responsible for defining what we now know as contemporary bluegrass guitar playing. He has managed to incorporate all the elements of rhythm, syncopation, phrasing, punctuation and most especially, improvisation into a tightly knit and coherent string of notes that has to be heard to be appreciated. He has set precedence for what the standard for a modern guitar break should sound like, and more frequently than not, flashy guitar breaks of the 21st century are built around Tony-isms.

In summary, guitar is where most of us (yours truly included)

started in bluegrass. Further, many of us can play a few chords and

fill in a bit on rhythm. But bluegrass guitar backup and flatpicking

lead is far more involved than anyone might have imagined and an absolutely

necessary part of great bluegrass.

[1] The bluegrass rumor mill has suggested that Jimmy Martin showed JD Crowe exactly which notes to play at the beginning of Hold What You Got. It seems as if Jimmy had the same taste in banjo notes as he did in fancy footwear and checkered head coverings.